AbstractPurposeBreast cancer rates are expected to rise with an increasingly aging society. However, research on breast cancer among elderly women is scarce. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the clinicopathological features of elderly women with breast cancer and assess their clinical outcomes following adjuvant chemotherapy.

MethodsPatients who underwent curative surgery for breast cancer between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2014 were retrospectively reviewed (n=1,865). The clinicopathological features, comorbidities, and survival outcomes were compared among three age groups (<55, 55–64, and ≥65 years). Subgroup analyses were also performed according to adjuvant chemotherapy status (i.e., administered or forgone) and need.

ResultsThe median age of the patients (n=1,865) was 51.7 years, and 231 (12.3%) patients were ≥65 years of age (defined as elderly). The median follow-up period was 56 months. The tumor characteristics were similar among the three age groups, except for tumor size and progesterone receptor status. The five-year overall survival rate was significantly poorer in elderly patients (87.5%) than in the younger groups (<55 years: 94.1%; 55–64 years: 93.2%) (p=0.002). Elderly patients received significantly less frequent adjuvant chemotherapy than the younger patients (p<0.001). Not all elderly patients in need of adjuvant chemotherapy were administered chemotherapy. Those administered adjuvant chemotherapy had significantly higher five-year overall survival rates than that of the non-administered patients (86.5% vs. 66.5%, p=0.014) and marginally longer breast cancer-specific survival (87.9% vs. 73.5%, p=0.07). Elderly patients who did not undergo chemotherapy had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus than those who did.

INTRODUCTIONAccording to the Global Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence (GLOBOCAN) report, breast cancer was the second most common malignancy worldwide in 2018, with 2,088,849 new cases diagnosed. It is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. According to Korean nationwide cancer statistics, breast cancer was the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer overall in 2015, with 19,219 new cases, and was the second most common cancer among women [2]. Further, a recent ‘Statistics Korea’ report stated that the proportion of elderly individuals (aged ≥ 65 years) with breast cancer was 14.3% in 2018, which is expected to rise to 41.0% by 2060 because of the declining birthrate and aging population [3]. Women’s life expectancy is also expected to increase from 85.7 years in 2017 to 91.6 years in 2067 [4].

According to the current demographic trends, the number of elderly women diagnosed with breast cancer will increase over the next decade. However, only limited data are available on the treatment modalities in elderly patients with breast cancer because such age groups are excluded from clinical trials related to systemic therapy [5]. Despite the lack of data, many physicians consider age as an important determinant of adjuvant therapy, and therefore, modify their treatments accordingly. Owing to the presence of comorbidities, the need for social support and functional status, elderly breast cancer patients are often undertreated [6]. Additionally, elderly patients generally show a passive attitude towards cancer treatment [7].

Considering the importance of proper treatment in an aging society and the apparent undertreatment of elderly patients with adjuvant chemotherapy, we analyzed the clinicopathological characteristics, comorbidities, and post-adjuvant chemotherapy survival outcomes of elderly patients with breast cancer, and compared these features to those of other age groups.

METHODSPatientsIn this retrospective single-center study, we reviewed the data from the electronic medical records of 1,865 patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer who underwent curative surgery at the Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea between 2009 and 2014. The investigated clinicopathologic factors included the surgical method, TNM (tumor, node, and metastases) stage, histologic type, histologic grade, and the expression statuses of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), and Ki-67. TNM staging was performed according to the guidelines of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition [8]. Comorbidities were evaluated according to the classification of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) as well as the presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and cerebrovascular disease.

Patients were categorized into three age groups: <55 years, 55–64 years, and ≥65 years (the elderly group). The two younger age groups were separated according to the menopausal status. Considering the median age at natural menopause (ANM) in South Korea and the menopausal period, we considered dividing the first two groups at the age of 55 years [9]. Each age group was sub-divided into four groups according to the chemotherapy recommendation and whether chemotherapy was actually administered: not needed/not administered, not needed/administered, needed/not administered, and needed/administered. The criteria for recommending chemotherapy were as follows: axillary lymph node metastasis, triple negative breast cancer with a tumor larger than 0.5 cm, HER2-positive cancer with a tumor larger than 1 cm, and ER-positive cancer with a tumor larger than 1 cm and Ki-67 staining greater than 30% or ER-positive cancer with a tumor larger than 5 cm and Ki-67 staining lower than 30%.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles laid in Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethical Committee of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea (IRB No. KC18RESI0774).

Statistical analysisDescriptive analyses were performed for univariate analysis of clinicopathologic characteristics using Pearson’s X2 test, and a p-value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of surgery to the date of breast cancer recurrence. Breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) was determined as the length of time between the date of surgery and the date of death from breast cancer itself. Differences in survival were analyzed using the log-rank test and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS/STAT 14.3 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, USA).

RESULTSAmong 1,865 patients, 231 (12.3%) were 65 years of age or older. Comparison of the clinicopathologic features of each age group is shown in Table 1. More than half of the women aged ≥65 years underwent mastectomy (51.9%) compared with one-third of the women aged <65 years. Women aged <55 years had higher tumor stages than did the older women. No significant differences were observed in nodal status, histologic type, and grade among the three age groups. In addition, there were no differences among the age groups in terms of ER status, HER2 status, and Ki-67 expression levels. Almost half of the women in the ≥65 years group were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (46.8%) compared to over 70% of younger women (71.8% of women <55 years and 73.3% of women aged 55–64 years).

Elderly patients received less frequent adjuvant chemotherapy than the younger women, irrespective of the recommendation (Table 2). In the “chemotherapy needed” groups, chemotherapy was not performed in 15.2% and 14.5% of women <55 years and 55–64 years, respectively, compared to 37.5% of women aged ≥65 years. Age was the only differentiating factor while comparing the clinicopathologic factors of women >65 years according to chemotherapy recommendation and administration (Table 3). In the “chemotherapy needed” groups, women who did not undergo chemotherapy were significantly older than those who did (mean age: 73.1 years vs. 68.2 years, p=0.019). Diabetes mellitus was more prevalent in elderly women who did not undergo chemotherapy than their counterparts who received chemotherapy (16.3% vs. 9.0%, p=0.038) (Table 4). There were no significant differences in other comorbidities related to the receipt of chemotherapy in older women.

Overall, the median follow-up period was 56 months (range, 1–109 months). The OS, BCSS, and RFS rates among the age groups have been presented in Figure 1. Compared to women <65 years of age, the OS rate was clearly poorer among elderly women; the five-year OS rates in the <55 years, 55–64 years, and ≥65 years age groups were 94.1%, 93.2%, and 87.5%, respectively (p=0.002). BCSS was also marginally poorer in elderly women; the five-year BCSS rates in the <55 years, 55–64 years, and ≥65 years age groups were 95.1%, 95.4%, and 91.1%, respectively (p=0.06). However, RFS rates did not differ among the age groups.

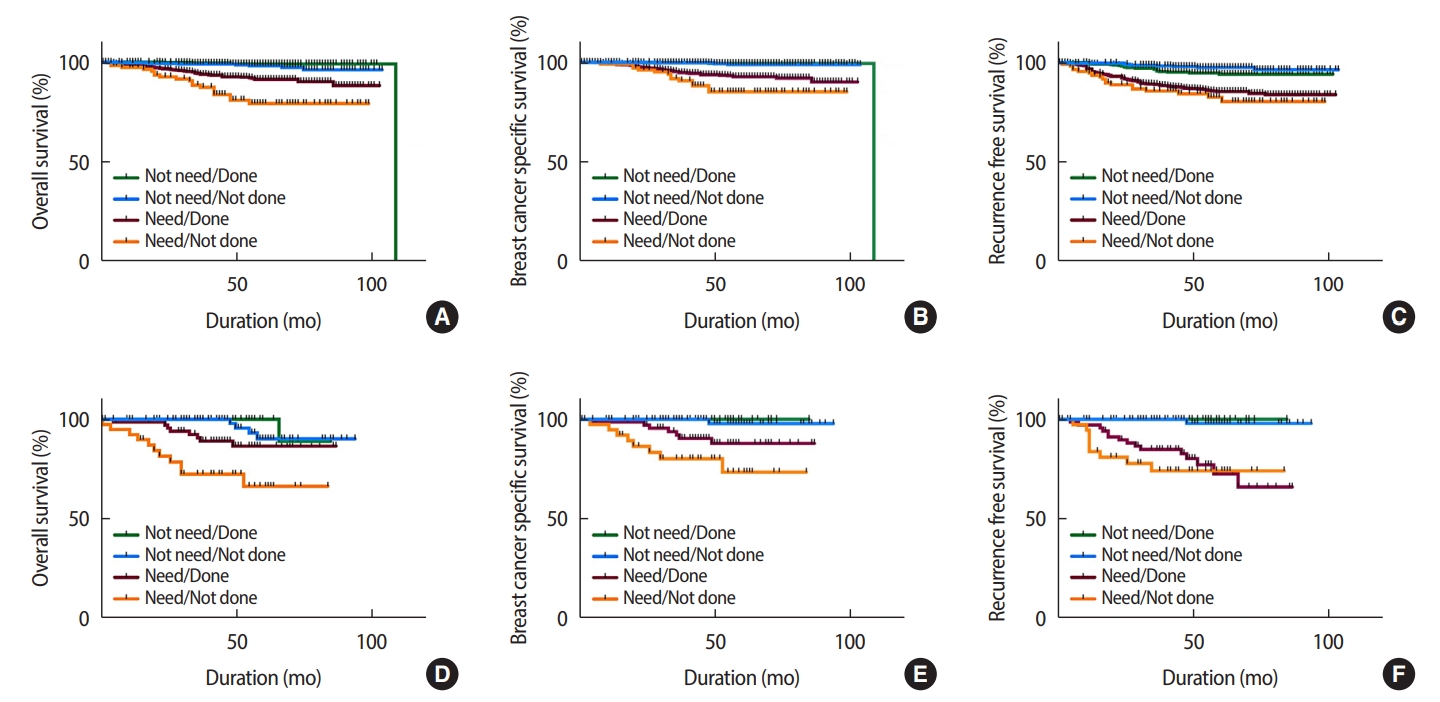

Detailed survival analysis according to adjuvant chemotherapy recommendation, receipt of chemotherapy, and age groups has been shown in Figure 2. Among all age groups, the patients who were recommended for chemotherapy had significantly poorer survival than those who were not recommended for chemotherapy. Among younger patients (<65 years), OS and BCSS rates were significantly lower in the needed/not administered group than in the needed/administered group (78.8% vs. 91.4%, p<0.001 and 85.2% vs. 92.7%, p=0.032; Figure 2A, 2B). RFS showed no significant difference in the needed/not administered group and the needed/administered group (82.6% vs. 85.4%, p=0.331; Figure 2C). Among elderly patients (≥65 years), the needed/not administered group had a significantly shorter OS than did the needed/administered group (66.5% vs. 86.5%, p=0.014; Figure 2D). However, BCSS was marginally lower in the needed/not administered group than in the needed/administered group (73.5% vs. 87.9%, p=0.07; Figure 2E). However, RFS showed no significant difference in the needed/not administered group and the needed/administered group (74.2% vs. 72.7%, p=0.539; Figure 2F).

DISCUSSIONThe findings of our study suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy contributes to improved survival rates at all ages, including elderly women ≥65 years of age. The patients recommended for adjuvant chemotherapy showed longer OS and BCSS in all age groups after chemotherapy was administered. These findings suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival rates in women of all ages, including elderly patients. The patients who were not recommended for adjuvant chemotherapy showed similar survival rates. These findings support that our adjuvant chemotherapy criteria were reasonable.

The clinicopathologic features of elderly breast cancer patients in our study were similar to those of younger women. Previous studies have shown that older women have more favorable tumor characteristics including smaller tumor sizes, a higher frequency of ER-positivity, and a lower frequency of HER2 overexpression [10,11]. However, this was not consistent with our study, in which elderly women presented with tumor features similar to those of women younger than 55 years. Further, although tumor size was similar among all age groups, elderly patients underwent mastectomies more frequently, which was also observed in previous studies [6,12].

Several studies have shown that elderly patients with breast cancer are undertreated in terms of adjuvant chemotherapy as compared to younger patients [13-16]. One study found that elderly patients (≥65 years) received adjuvant chemotherapy significantly less frequently than their younger (<65 years) counterparts (46.7% vs. 80.4%, p<0.001) [13]. Wallwiener et al. also found that elderly patients (≥65 years) in both the intermediate- and high-risk categories (based on the 2005 St. Gallen Consensus Conference criteria) received adjuvant chemotherapy less frequently (p<0.001) [16]. Our study also showed that the frequency of adjuvant chemotherapy was significantly lower in elderly patients with breast cancer than in younger patients, including patients specifically recommended for adjuvant therapy. This may be related to higher prevalence of comorbidities in older individuals as well as to additional caution taken by the surgeons. In practice, however, the differences in comorbidities among patients of different age groups were not significant; only diabetes mellitus was significantly more prevalent in elderly subjects than in younger individuals in our study.

The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients remains controversial. Several retrospective studies have found that adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival in elderly patients with breast cancer [17-20]. The French Adjuvant Study Group 08 trial showed that weekly administration of epirubicin plus tamoxifen was more effective than tamoxifen alone in extending disease-free survival, with tolerable toxicity [21]. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study (CALGB 49907) trial, which compared standard chemotherapy to capecitabine, revealed superior RFS rates among patients receiving standard chemotherapy, supporting the notion that adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival among older women [20]. However, neither of these trials demonstrated any differences in OS among their different treatment groups [20,21]. The survival benefit conferred by adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients has also been challenged in retrospective studies [5,22]. In the present study, we evaluated the role of adjuvant chemotherapy based on the ‘need’ of the patients according to their tumor characteristics. As expected, adjuvant chemotherapy did not influence the survival of patients with favorable clinicopathological characteristics. However, elderly women with poor prognostic features experienced marginally improved BCSS following adjuvant chemotherapy. OS was also longer in elderly patients who underwent chemotherapy when needed, although the data were biased owing to the age-related comorbidities and disabilities.

The limitation of our study is that it was retrospective and the number of patients was small (although not necessarily so for a single institution). The follow-up period was also relatively short for OS analysis. Although we performed a rigorous review of medical records, we were unable to ascertain the detailed reasons for forgoing chemotherapy in elderly patients. Comorbidities might have also been underestimated owing to the retrospective nature of this study.

In conclusion, elderly patients with breast cancer had characteristics similar to those of younger patients. Consistent with previous studies, we found that elderly patients with breast cancer were undertreated. Active and persistent recommendations of standard adjuvant chemotherapy are required to improve survival outcomes in elderly patients.

Figure 2.(A) Overall survival curves according to necessity of chemotherapy in age <65. (B) Breast cancer specific survival curves according to necessity of chemotherapy in age <65. (C) Recurrence free survival curves according to necessity of chemotherapy in age <65. (D) Overall survival curves according to necessity of chemotherapy in age ≥65. (E) Breast cancer specific survival curves according to necessity of chemotherapy in age ≥65. (F) Recurrence free survival curves according to necessity of chemotherapy in age ≥65.

Table 1.Patient characteristics according to age group (n=1,865)

Table 2.Distribution of recommendation and its performance of chemotherapy by each age group (n=1,865) Table 3.Clinicopathologic analysis by recommendation of chemotherapy in elderly (n=231)

Table 4.Comorbidity according to chemotherapy or not in elderly (n=231) REFERENCES1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424.

2. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2015. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:303-16.

3. 2018 Statistical report on the aged. Daemon: Korea Statistical Information System (KOSIS). Korea National Statistical Office; http://kostat.go.kr/assist/s.ynap/preview/skin/doc.html?fn=synapview370779_1&rs=/assist/synap/preview. Accessed Mar 1st, 2019.

4. 2017 life table. Korean Statistical Information Service; http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1B41&vw_cd=MT_ETITLE&list_id=A5&scrId=&seqNo=&language=en&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=A6&path=%252Feng%252Fsearch%252FsearchList.do. Accessed Mar 1st, 2019.

5. Lee HCh, Chen WY, Huang WN, Cheng KO, Tian YF, Ho ChH, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly breast patients in Taiwan, a hospital-based study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016;17:4591-7.

6. Tesarova P. Breast cancer in the elderly-Should it be treated differently? Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 2012;18:26-33.

7. Lavelle K, Todd C, Moran A, Howell A, Bundred N, Campbell M. Non-standard management of breast cancer increases with age in the UK: a population based cohort of women>or =65 years. Br J Cancer 2007;96:1197-203.

8. Hortobagyi GN, Connolly JL, D’Orsi CJ, Edge SB, Mittendorf EA, Rugo HS, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2017. p 589-636.

9. Park CY, Lim JY, Park HY. Age at natural menopause in Koreans: secular trends and influences thereon. Menopause 2018;25:423-9.

10. Diab SG, Elledge RM, Clark GM. Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:550-6.

11. Syed BM, Green AR, Paish EC, Soria D, Garibaldi J, Morgan L, et al. Biology of primary breast cancer in older women treated by surgery: with correlation with long-term clinical outcome and comparison with their younger counterparts. Br J Cancer 2013;108:1042-51.

12. Dimitrakopoulos FI, Kottorou A, Antonacopoulou AG, Makatsoris T, Kalofonos HP. Early-stage breast cancer in the elderly: confronting an old clinical problem. J Breast Cancer 2015;18:207-17.

13. Kim HK, Ham JS, Byeon S, Yoo KH, Jung KS, Song HN, et al. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of elderly breast cancer patients: experiences at a single institution in Korea. Cancer Res Treat 2016;48:1382-8.

14. Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Laissue P, Neyroud-Caspar I, Schafer P, et al. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3580-7.

15. Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Blagojevic S, Vlastos AT, Vlastos G. Older female cancer patients: importance, causes, and consequences of undertreatment. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1858-69.

16. Wallwiener CW, Hartkopf AD, Grabe E, Wallwiener M, Taran FA, Fehm T, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with primary breast cancer: are women >/=65 undertreated? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2016;142:1847-53.

17. Park JH, Choi IS, Kim KH, Kim JS, Lee KH, Kim TY, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in elderly patients with metastatic breast cancer: a multicenter retrospective study. J Breast Cancer 2017;20:368-77.

18. Jung SP, Lee JE, Lee SK, Kim S, Choi MY, Bae SY, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival of elderly korean patients with breast carcinoma. J Breast Cancer 2012;15:296-305.

19. Du XL, Zhang Y, Parikh RC, Lairson DR, Cai Y. Comparative effectiveness of chemotherapy regimens in prolonging survival for two large population-based cohorts of elderly adults with breast and colon cancer in 1992-2009. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1570-82.

20. Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Theodoulou M, Mauer AM, Kornblith AB, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2055-65.

21. Fargeot P, Bonneterre J, Roche H, Lortholary A, Campone M, Van Praagh I, et al. Disease-free survival advantage of weekly epirubicin plus tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone as adjuvant treatment of operable, node-positive, elderly breast cancer patients: 6-year follow-up results of the French adjuvant study group 08 trial. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4622-30.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||